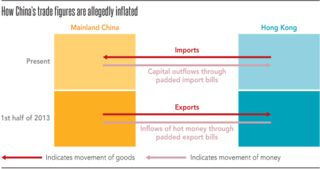

HONG KONG -- Doubts have reemerged about padding of China's trade figures. In the first half of 2013, speculative money flowed into mainland China through the use of inflated export bills. The scheme, designed to get around China's strict cross-border capital controls, has since withered, thanks to a government crackdown. But now, the flow is reversed. Such bill-padding is now used to withdraw capital from mainland China.

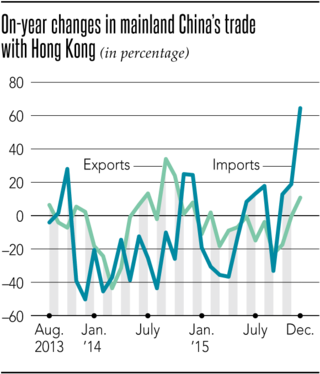

On Jan. 13, economists and investors were astounded by China's trade statistics for December, published by the General Administration of Customs. Trade values with Hong Kong were suspiciously higher than a year before. In particular, imports from the special administrative zone surged by as much as 64% to $2.16 billion, despite a decline in the value of overall imports to mainland China.

A research team at Nomura International (Hong Kong) said that the import figure is unusually high, and that capital outflows from the mainland in the form of imports from Hong Kong are probably skewing the data.

The need for such a scheme stems from the central government's strict controls on the movement of capital in and out of the mainland. The authorities believe that restricting the flow of money in the form of securities, real estate or other investment vehicles -- that is, money not counted as trade -- would help avoid economic turbulence because such restrictions make it difficult to liquidate yuan-denominated assets amid a weaker currency or tumbling stock market, for instance.

Business owners and investors thus use their non-investment transactions as a cover to escape the capital controls. Some companies in mainland China deliberately overvalue goods imported from Hong Kong in their filings so as to free up capital. This method is known as invoicing, in which traded goods are exported from the mainland to Hong Kong and later reexported to the mainland with their prices inflated each time. The name is derived from the fact that they use invoices, or documents itemizing goods or services traded along with prices, to their own advantage.

The timing of the spike in imports from Hong Kong roughly coincides with the time when the Chinese yuan began sliding further down. The yuan came under increased pressure after the International Monetary Fund decided on Nov. 30 to include the currency in its Special Drawing Rights basket. A view spread across markets that the yuan's entry to the reserve currency basket will make it difficult for Chinese authorities to step in to prop up the yuan openly as it has done in the past. The slowing economic growth there, coupled with a U.S. interest rate hike accelerated selling of the currency in favor of the greenback.

For investors rushing for the exit, invoicing emerged as a way of pulling money out of the mainland while slipping through regulations. Signs were already apparent in prior data. Imports from Hong Kong to mainland China actually fell year on year in the first seven months of 2015 by 13%. But they started to rise again after August, more than cancelling out earlier declines. For the entire year, imports were up 1.2% compared to a year before. Considering the sudden devaluation of the yuan in August 2015 by the People's Bank of China, the central bank, invoicing may have already been in full play around that time.

In 2013, things were going in a completely opposite direction. At that time, China was still enjoying higher growth and the U.S. was easing its monetary policy to an extreme degree. Hot money left idle for investment opportunities amid low interest rates across the globe sought every possible way to get into the Chinese market. As a result, money flooded into the country through padded Chinese export bills. In each of the five months from December 2012 to April 2013, the value of Chinese exports grew by a double-digit rate, which prompted China's State Administration of Foreign Exchange to strengthen its oversight in June 2013, a rare move.

Whether China's recent trade figures are artificially inflated will become clear when the Hong Kong government releases its trade statistics for December on Jan. 26. Last time, inconsistency between the official figures from the two governments generated much skepticism.

If imports and exports are indeed found to have been padded, that would not only undermine the reliability of statistics by the mainland government but would also intensify the view that the Chinese economy is doing worse than what statistics show.

Overall exports and imports in December were down 1.4% and 7.6%, respectively, according to the data Jan. 13. Still, the numbers beat market expectations, which then briefly lifted shares in the U.S. and European markets. But statistical numbers from the mainland government are no longer acceptable at face value. Fears are growing amid the sounds of a creaking Chinese economy.